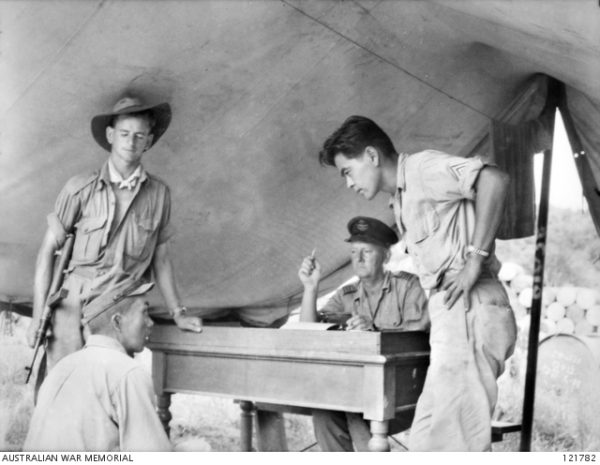

Some of the emblematic pictures associated to Japanese World Warfare II atrocities in opposition to Australians exhibits the post-war interrogation of Navy Police (Kenpeitai) Sergeant Hosotani Naoji close to Sandakan, northeast Borneo, in October 1945. Sandakan was the positioning of a Japanese labor camp established in 1942 for Australian and British prisoners of battle (POWs). By January 1945, with an allied invasion of north Borneo seemingly imminent, the camp commanders had been ordered to ship its prisoners by means of 260 kilometers of jungle and mountainous terrain to Borneo’s Ranau district.

Over 5 months, successive teams of malnourished prisoners had been marched by means of the jungle. Prisoners who fell out had been shot, bayoneted, or bludgeoned to demise. These too unwell to affix the marches had been left to die or had been killed. The emaciated males who reached Ranau died off beneath a regime of compelled labor, hunger rations, and brutality; in August 1945, the final survivors had been shot. 1,787 Australian and 641 British prisoners are estimated to have died in the course of the Sandakan Dying Marches. Six Australian escapees survived.

Hosotani confessed to taking pictures 5 ethnic Chinese language civilians suspected of aiding native guerrillas and two Australian POWs on the best way to Ranau. He was convicted of battle crimes and executed by firing squad in March 1946, one in every of 137 Japanese and colonial Korean servicemen sentenced to demise and executed by Australian army courtroom orders.

In July 2014, in a speech to the Australian Parliament, Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo talked about Sandakan and the Kokoda marketing campaign of 1942, a protracted battle through which Australia’s armed forces repelled a Japanese advance into New Guinea. Whereas talking of “staying humble in opposition to the evils and horrors of historical past” and expressing the Japanese individuals’s “most honest condolences in the direction of the numerous souls of those that misplaced their lives” Abe didn’t explicitly apologize for Japan’s previous battle crimes in opposition to Australians.

Australia’s then-Prime Minister Tony Abbott, international coverage students, and main media retailers responded positively to Abe’s speech, with its vows by no means once more to repeat “the horrors of the previous,” and its imaginative and prescient for nearer financial and safety ties between Australia and Japan primarily based on “shared values.” Abe and Abbott later signed an settlement on the “switch of protection gear and know-how” signaling a better strategic partnership between Japan and Australia. It fell to the Australian Protection Drive veterans’ group, the Returned and Companies League of Australia (RSL) — a long-time custodian of Australian battle remembrance — to specific disappointment on the lack of point out of Japan’s battle crimes.

In his speech, Abe invoked Sandakan and Kokoda, understanding their place in Australia’s battle reminiscence pantheon. However he additionally calculated rightly that up to date pragmatism in Australia-Japan relations was prevailing over any residual anti-Japanese battle reminiscence, amid stirrings of hysteria over China’s assertiveness in Asia. In fact, as Abe additionally knew, such pragmatism was a very long time within the making in post-war Australia-Japan relations. In mild of the battle and colonial reminiscence controversies in Japan’s relations with its neighbors, it’s helpful to know how Australians have labored out their very own battle reminiscence in relations with Japan and to ask what classes may be drawn from that understanding.

The very first thing to notice is that World Warfare I looms giant in Australia’s government-sponsored and widespread battle remembrance. Memorialization of Australia’s battle with Japan has grown in its shadow. Virtually from the time Australian and New Zealand troopers or “ANZACs” commenced their First World Warfare participation in April 1915 in the course of the Gallipoli Marketing campaign in Turkey, their preventing prowess and nationwide characters had been being mythologized by battle correspondents, artists, and filmmakers.

By the battle’s finish an “ANZAC legend” commemorating sacrifice — and army triumph — was turning into a civil faith in each nations. In Australia significantly, the baptism of fireside at Gallipoli got here to be seen because the “beginning of the nation,” beneath the British Empire’s protecting mantle. Remembrance of those that served in subsequent wars was assimilated into government- and RSL-sponsored monuments, ritual commemorations, and widespread iconography established throughout and after World Warfare I.

In 1992, Labor Prime Minister Paul Keating tried to distance Australian battle commemoration from its entanglements with the “principally imperial” European conflicts of the world wars. Throughout a well-publicized go to to New Guinea, he nominated the Kokoda marketing campaign as a brand new focus for Australian battle remembrance. Keating differentiated Kokoda from the European conflicts by asserting — on doubtful historic grounds — that at Kokoda Australians had fought to “forestall an invasion of Australia.” For Keating, this new focus was extra applicable for a now multicultural, Asia-oriented Australia.

The brand new concentrate on Kokoda, and on Australia’s Pacific Warfare expertise, in the end contributed to a diversification quite than reorientation inside Australian battle remembrance. Due to Eighties movies like Peter Weir’s “Gallipoli” and authorities promotion, ANZAC mythology had already been up to date in a brand new “battle reminiscence increase,” accommodating extra egalitarian, progressive, and anti-British imperialist outlooks. The Kokoda monitor in New Guinea joined, quite than supplanted, ANZAC Cove in Turkey as a website of battle pilgrimage for younger Australian vacationers. With the late Twentieth-century battle reminiscence emphasis on struggling and trauma, Australian troopers might be memorialized as victims of bungling British generals in World Warfare I, and of vicious Japanese jail camp guards in World Warfare II. However in at this time’s extra diversified battle memory-scape, there may be little style for particularized resentment in opposition to the Japanese.

Additionally noteworthy, then, is the decline of widespread anti-Japanese battle reminiscence. Anti-Japanese sentiment had in actual fact encroached into the ANZAC legend at its inception. Historians have proven that White Australia Coverage legal guidelines formulated in 1901 to exclude non-White immigrants had been partly impressed by fears of Japanese invasion and racial takeover. Australia’s World Warfare I Prime Minister Billy Hughes alluded to Japan — then a wartime ally — in declaring the battle in Europe to be a battle for White Australia. On the Paris Peace Convention in 1919, he trumpeted Australia’s wartime sacrifice and opposed a racial equality treaty modification proposed by the Japanese delegation. Hughs’ White Australia advocacy had the full backing of the RSL’s predecessor, the Returned Troopers and Sailors League. In 1941, nationwide leaders additionally framed the Pacific Warfare as a protection of White Australia.

After 1945, public hostility to renewing relations with Japan mirrored anger over battle atrocities, fears of Japanese resurgence, and “White Australia” racism. Anxieties continued within the RSL about Japanese financial infiltration and migration near Australia whilst peace and commerce treaties had been concluded with Japan within the Fifties. Personified by abrasive spokesmen like Bruce Ruxton, the RSL remained a distinguished critic of Asian immigration and Japanese funding for many years after the ultimate dismantlement of the White Australia Coverage in 1973.

In the long run, reconciliation efforts and rising business relations with Japan helped dim bitter Pacific Warfare reminiscences. From the Nineteen Seventies, anti-Asian racism step by step abated as successive Australian governments accepted extra Asian immigrants and promoted multiculturalism, together with in official battle remembrance. Altering RSL attitudes had been signaled by an official Japan tour for its management in 2000, with a go to to Tokyo’s controversial Yasukuni Shrine. Japanese Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro’s 2002 go to to the shrine provoked criticisms from battle veterans and a few RSL leaders, however others expressed cautious understanding of Koizumi’s motives. In 2001 Tom Uren, a distinguished left-wing politician and former POW, and Jan Ruff-O’Herne, a former Dutch civilian captive in wartime Java kidnapped to and sexually abused in a Japanese “consolation station,” spoke for some Pacific Warfare survivors in expressing forgiveness.

Diversified battle reminiscence, the attrition of anti-Japanese resentment, and financial and strategic pursuits in East Asia all underwrite the present bipartisan pragmatism in Australia’s relations with Japan. Abe recalled in his 2014 speech that this pragmatism was manifested early in Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies’ reconciliatory gestures towards his grandfather, Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke, whom Menzies invited to Australia in 1957 to signal a commerce treaty. Australia-Japan commerce elevated quickly thereafter, foreshadowing the twenty first century strengthening of strategic ties.

Can states whose relations with Japan are burdened by fraught colonial and battle reminiscence politics – akin to South Korea – study from the international coverage pragmatism of peer Asia-Pacific nations like Australia? Maybe not. South Korea’s Japanese international coverage largely stays hostage to tradition wars between right- and left-wing Korean constituencies over the colonial and post-colonial previous, waged with far larger depth than Australia’s personal “historical past wars.” South Korean governments nonetheless lack the political capital to prioritize international coverage pragmatism over a robust anti-Japanese nationalism, although altering East Asian geopolitics might incentivize a decision to that deadlock.

In the meantime, classes from Australia’s Pacific Warfare memorialization are relevant elsewhere. Australian leaders can specific disapproval when Japanese right-wing factions alienate regional neighbors by denying previous battle crimes and colonial abuses, of their makes an attempt to revive nationalism and justify elevated army energy. Current-day instability in East Asia supplies higher causes for Japan, Australia, and like-minded regional states to collaboratively improve their army capabilities. However reminiscence of the horrors inflicted by Japanese militarism may inform Australian efforts to take care of peace within the Asia-Pacifi, and assist counter China’s rise as a revanchist, militarizing energy.